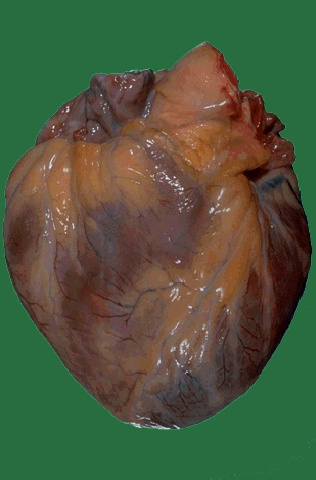

This is a human heart. Pretty gross, huh? Well, I have a story to tell you about a heart...my heart, and how it attacked me on May 29, 1993. There is a lesson, but I'll leave it until the end. For now, read the disclaimer and just pay attention to the story.

When I was 24 years old, I weighed 333 pounds. I'm a fairly big guy, but that was at least 100 pounds more than I should have weighed according to all the doctor's charts. How I came to be in this extremely unhealthy condition was simple: I ate too much and I didn't exercise. I'd been too busy going to college, thinking deep thoughts, and watching lots of "educational" TV. I had also recently married a woman that made excellent biscuits; they were especially good smothered in butter and raspberry jam. To put it simply, I "let myself go." I quit paying attention to my weight, and while I wasn't looking, it got out of control.

In May of 1991, I applied for a summer job with the city recreation department. Part of the application process was a physical exam, which I failed. My blood pressure was moderately high, and until I had it under control, the city would not hire me. I went to the doctor, and he told me what I knew to be true, but that didn't stop it from stinging: "Mr. Thompson, you are obese. Obesity contributes to high blood pressure." He said it so matter-of-factly; it wasn't meant as an insult, just a simple fact. And it was true. And the truth hurt.

That doctor gave me some medication that helped control my blood pressure, so I was able to work the city recreation job that summer, but I also resolved that I was going to get healthy. By this time, my wife was pregnant with our first child, and I decided that I wanted to live long enough to see that child grow up. As my wife's belly grew, mine shrank. I vowed to lose 100 pounds. I was going to get healthy.

I bought an exercise bike which I put in the basement of our apartment. I rode it hard for an hour every day--headphones on, heavy metal blasting my eardrums, legs pumping like pistons of sausage, and sweat pouring in buckets from every pore on my body. When my workouts were finished, my gym clothes were soaked through. My wife wouldn't even let me put them in the regular laundry hamper; they had to go straight into the washing machine. My routine did not vary much, and at times it was boring, but I stayed with it religiously. Every day after school I was on the bike for an hour.

Then I went on a diet. It was simple: I quit eating fat. No cheese, no butter, no fried food, no pizza...and no enjoyment. I had a bowl of Grape Nuts for breakfast with skim milk. (The only difference between Grape Nuts and little brown rocks is that Grape Nuts have a higher nutritional value...and are twice as hard.) I had a low-fat turkey sandwich and a handful of carrots for lunch. I had some variety of rice and vegetables for dinner. Insane as this may seem, I did it every day for a year. I never strayed from the routine. I was obsessed. But it worked. (Update 2017: This obsessive tendency came into play 24 years later when I decided to change my life again. Details follow.)

I remember the day I weighed in at the doctor's office a couple months after I made my resolution. The scale read 298. Still huge, but I had lost 35 pounds! I walked around for two days picking up things that weighed 35 pounds and saying to anyone who would listen, "I've lost this much weight! Here, lift it! See how heavy that is?!" The quick success prompted me to continue my quest for good health. By the time my daughter was born in the summer of 1992, I was down to 250 pounds. At this point, people had started to notice: "Wow! You've lost weight! You're looking great! How'd you do it?"

But it wasn't good enough for me. My vow was to lose 100 pounds, and I still had 15 to go. I had hit what the dietician called a "plateau." Losing weight is simple in theory: Burn more calories than you consume. When you are packing around massive amounts of excess blubber, as I was, this isn't hard to do, especially when you radically change your lifestyle and eating habits, as I had. But as the blubber disappears and muscle develops, it becomes harder to continue to lose weight so quickly because you simply don't have as much extra weight to lose. And this is where I found myself as I went into my fourth year of teaching in the fall of 1992. My weight stalled at 250.

This also happened to be the year that the school district was experimenting with year-round scheduling at the junior high level, and I was part of the experiment. To complicate matters further, I was teaching an extra class each day to earn enough money so my wife could stay home with our daughter and not have to work full time as she had done before. I was worn out all the time, and I started drinking coffee (no cream or sugar) to stay awake. It was a very stressful year, but I didn't resort to overeating, and I continued my fanatical exercise routine. In fact, I even purchased a rowing machine to augment my workouts. It looked good next to the bike in the basement.

I was on B-track that year, and we had a three week break from the middle of May until the first week in June. I looked forward to the time off, and I was enjoying it fully. We didn't have enough money to take long vacations, but I liked having no responsibilities for a couple weeks. I would sleep in, get my exercise out of the way as soon as I got up, and then spend the rest of the day playing with my daughter, who was almost walking by that time. Things were good...until May 29.

It was the Saturday morning of Memorial Day weekend, and I still had a week before I had to go back to school. I slept until 9 and then went down into the basement for my workout. I got on the rowing machine as I had done many times before. Twenty minutes into the workout, sweat was rolling into my eyes and my shirt was almost completely damp. I felt strong--invincible. Then something went wrong.

I was lightheaded. At first it felt like that mild dizziness you get when you stand up too fast, and I thought it would clear away when I slowed my workout. But it got worse. I could see the brown, checkerboard patterns at the edges of my vision, and I realized I was about to pass out. I stopped rowing and staggered off the machine, trying to stand up and take a deep breath. Instead, I stumbled headlong into the exercise bike. I remember thinking how bad it should have hurt (there was later a huge bump on my head), but since I was nearly unconscious I felt nothing.

The linoleum floor was cold against my sweaty back, and I realized I was panting for breath. It was like trying to breathe syrup. I was gasping as hard as I could, but very little oxygen seemed to be coming in. "What's happening?" I groaned. Then, I heard my own voice from somewhere deep in my mind reply, "You're dying." This is when sheer terror set in because somehow I knew that voice spoke the truth.

A few moments on the floor must have provided my brain with enough oxygen to clear my head, and I knew I had to get help. My wife was upstairs with my daughter. The door at the top of the stairs was closed, so she hadn't heard me thrashing around and crashing into things. As I could barely draw a breath, yelling was impossible. I realized that if I could not get to her, I would probably die alone on the basement floor. Fear pulled me to my feet. I staggered to the stairs, going face first into the wall at one point, and grabbed the railing. With supreme effort, I dragged myself up the stairs, each step a mountain. About half way up the stairs, I first noticed the angry sting in my chest.

A bee was lose under my breastbone, and he had let me have it from the inside! I was nearly to the top of the stairs, grasping for the doorknob that would lead me to help, when I became aware that it wasn't just one bee, but an entire hive. The door at the top of the stairs had a square window in it, through which I could see my wife in the kitchen. I lurched to the top step, and she heard me crash against the door. Puzzled, she turned and opened the door. I groaned, "Something's wrong," and crashed, dead weight, to the floor.

I did not lose consciousness, but I was still gasping for breath, and the pain in my chest was now almost unbearable. I remember seeing an episode of The Simpsons in which Homer described the pain of a heart attack as something like "5000 flaming knives stabbing me in the chest." Homer understated. My chest was burning as though there were a ball of molten lava under my ribs. My wife called 911, and I lay on the kitchen floor for five minutes until the ambulance arrived. While my wife was on the phone, my 10-month old daughter climbed up on me and wanted to play. Under any other circumstances, it would have been cute. My head cleared as I was able to get some air into my lungs, but the pain increased. I was pretty sure by this time that I was having a heart attack. The problem was getting anyone else to believe me.

"Twenty-six year olds don't have heart attacks," the ambulance driver said as he calmly stood in the living room taking my medical history. A team of paramedics hooked me up to a portable EKG machine, checked my vital signs, and prodded me mercilessly to figure out what was wrong. Despite my continual suggestion that it was a heart attack, they would not make such a diagnosis. They did, however, recognize that something was seriously wrong with me, and they hefted me onto a stretcher and took me to the ambulance. A trip to the hospital was in order.

If you have never been inside an ambulance (here's a story), you can't appreciate how sterile and cold it is. There are tubes and bottles and straps dangling from the walls, gauges and hypodermics, and the floor and ceiling are an icy, silver steel. It's like being fed into a cold metal box on a tray. I'll never forget the sinking feeling I had as I watched through the rear window while my apartment shrank into the distance as the ambulance pulled away. "What if I never come back here?" I wondered.

My wife had to take my daughter to stay with someone else before she could come to the hospital, so I took the long, cold ride with only a faceless paramedic at my side. He was nice, but I don't think he really believed there was anything wrong with me. He spoke in that condescending tone that adults sometimes take on when talking to small children. And there were no sirens! I was almost mad! They were casually driving along busy streets, stopping at all the red lights, not making any noise at all! I asked, "Why aren't we going faster?" as the pain in my chest had now settled in deep, and I was nearly in tears. "You'll be fine," was the only reply. "You're too young to have a heart attack."

The emergency room is a blur in my memory. Nurses drew blood and took my vital statistics. Technicians x-rayed my chest. Doctors conferred together behind a curtain. And at some point, my sweaty gym clothes were stripped away...and I mean completely. Somehow I ended up in one of those surgical gowns which is nothing more than an ill-fitting piece of cloth with four holes: two for your arms, one for your head, and one for your butt--I guess they need easy access to all parts of the patient.

I continued to insist that I was having a heart attack, but the preliminary blood test was negative. There is a chemical or enzyme which is released into the blood stream when a person has a heart attack, so elevated levels of this particular enzyme indicate that a heart attack has occurred. My levels were normal. More tests. More prodding. More conferences behind curtains.

After half an hour in the emergency room, my chest now clenched in upon itself in agony. I was hooked up to an I.V. and more blood was drawn. I remember being given some greenish concoction that was supposed to clear up my indigestion--yes, they actually thought it was indigestion! (If indigestion felt like this, Tums would have to contain morphine.) Then the results of the second blood test came back. Because I had come to the hospital so quickly, the enzyme which indicates a heart attack did not appear in the first blood test. The second test, however, indicated that my level of that enzyme was 10 times normal.

I'll never forget the look on the doctor's face. He was astounded. When he said it, it almost sounded like a question: "Mr. Thompson, you are having a heart attack."

| Now

seems like an appropriate time to tell you a little about what exactly a

heart attack is. We use the term a lot, but not very many people actually

understand it. I didn't until I had one. In simple terms, the

heart is a big muscle that pumps blood, which carries oxygen, to the

all the parts of your body. However, the heart also needs its own oxygen

supply to keep up all that pumping; that's where the coronary

arteries come in. These are the vessels on the outside of the heart

that feed oxygen to the heart muscle. If one (or more) of your coronary

arteries becomes blocked, thereby preventing blood (and oxygen) from reaching

the heart muscle, you are having a heart

attack.

What might cause a blockage in a coronary artery? Coronary artery disease (CAD) and/or arteriosclerosis (one form of which is atherosclerosis) is the most common cause of heart attacks. Some known causes of atherosclerosis are high levels of cholesterol in the blood, high blood pressure, and tobacco smoke. These contribute to narrowing and hardening of the arteries, which makes it difficult for blood to flow freely through them. The narrower arteries become, the more likely a heart attack becomes. It's a simple equation: no blood = no oxygen = no life. In my case, however, it was not CAD, but rather a thrombosis and/or an embolism that caused my heart attack. A thrombosis is a blood clot that forms inside one of the coronary arteries. An embolism occurs when the clot moves through the bloodstream until it lodges in a blood vessel and blocks circulation. If this happens in a coronary artery, as it did in my case, it's a heart attack. What caused my blood clot? No one knows, although some of my doctors speculated that it may have been caused by processing so much fatty acid out of my system over the previous two years. Somehow that may have injured the inside of one of the coronary arteries, causing the clot which broke loose during my round of vigorous exercise, which in turn blocked the artery and put me in the emergency room. Here's the bitter irony of it: I spent two years doing everything I could to prevent a heart attack, and it may have caused one! Was I angry about this? I'll give you one guess. |

And now that the diagnosis was official, the entire emergency room kicked into action for my benefit. I was first given a handful of children's aspirin, those little pink pills (which children really shouldn't take) that you chew to a sweet paste before swallowing them. Then a drug was injected into my I.V. that caused my body temperature to rise by about 1000 degrees. My face flushed and I felt like I was on fire. (I later discovered that the drug dilated my blood vessels so that blood could circulate more freely; this causes you to feel very hot.) And when the cardiologist arrived, we were off to surgery.

Surgery?! Yes, surgery! No, they weren't going to crack my ribs open and saw my heart out, but they were going to perform an operation known as an angioplasty. In this operation, a microscopic wire with a microscopic balloon on the tip is inserted--get this!--into your thigh and is then "threaded" up through your blood vessels all the way to your heart. When it gets to the place where the blockage is located, they open the balloon. This clears the blockage and allows blood to flow freely. Then they fill you full of clot-busting drugs to make sure the blockage dissolves. But I knew nothing about all this when they rolled me, on a gurney, down the sterile corridors of the hospital and into a large dark room.

I don't know what the machine is called, but it works like an X-ray machine. It is a huge, black thing that hangs from the ceiling and it displays pictures of your insides on two monitors at either side of the room. As one technician was positioning the huge, black thing above me, another was shaving my leg. Yes, you heard it right. Apparently the doctors needed a smooth clean surface into which they could insert the cardiac catheter, so my right thigh (as well as other more embarrassing spots) was cleanly buzzed. Then there was a sting in that same spot as they deadened the area into which the catheter was to be inserted. There's no pleasant way to say it: they stabbed me in the groin! (And since I was wearing the world's most immodest hospital gown, it wasn't too hard for them to do so.) Then came the dye.

No, not die. Dye. They injected some sort of dye into my bloodstream that showed up quite clearly on the monitors at which the doctors were now looking. I looked over and was stunned to see a black-and-white version of my guts, right in the center of which was a large, pulsating mass from which the neon dye was now pumping. That was my heart! The doctors traced the path of the dye through my coronary arteries, and way down at the bottom of my heart, the glowing path ended. Why? Because that's where the blockage was. Let the angioplasty begin!

I didn't feel them stick the catheter into my femoral artery (in my thigh) because the previous shot had taken effect and I was numb from the waist down. (My chest was still on fire.) I knew, however, that I had been pierced because a small jet of blood splashed the doctor's white lab coat. Then, on the wall monitor, I watched in black and white as the tiny wire was threaded up through my blood vessels, past many internal organs, into the heart, down through the small coronary arteries, right to where the glowing trail of dye stopped. The doctor said, "Get ready for relief." The tiny balloon expanded, the vessel opened up, the molten ball of lava in my chest was extinguished.

"Thank you." That was all I could say.

I spent six days in the hospital. The entire time I was hooked to what the nurses called a telemetry device to monitor my heart. This device was a black box about the size (and weight) of a brick that I wore on a strap around my neck. It had wires snaking out of it. These wires were attached to various places around my chest and under my arms. As long as I had this device on, any change in my heart rhythm showed up on a monitor at the nurses' station outside my room. I soon discovered that if I wanted quick attention from a nurse, all I had to do was yank one of the wires off my chest. This set off a loud alarm at the nurses' station, and three or four nurses would come running. (When they heard the alarm, they thought my heart had stopped.)

There are two things I distinctly remember about the hospital: the "tests" and the food. Because the doctors still could not believe that someone my age (26 at the time of the heart attack; although I "celebrated" my 27th birthday in the hospital) had heart trouble, I was subjected to every possible heart test they could think of. For one of them, radioactive isotopes were injected into my blood and I was then placed under a gigantic imaging device which took pictures of my heart pumping to see if it was normal. For the rest of my stay I was radioactive; there was a warning sign on my door that said, "Danger! Radiation! Pregnant women should not enter!" Then there was the treadmill test: they put me on a treadmill (still hooked to my telemetry brick) and made me run uphill until I was panting. The doctor told me that they were trying to induce another heart attack. When I seemed alarmed, he said, "Is there somewhere else you'd prefer to have a heart attack than in the hospital, ten steps from the cardiac care unit?" I saw his point, but that made it no less scary. What these and other numerous tests determined was that I had lost 3% of my heart muscle. (A little patch of my heart was dead, and it wasn't coming back...or so I believed at the time.) Compared to most people who have heart attacks, that wasn't too bad. I was told that I should be able to resume a normal life after recovery, and that I had no signs of coronary artery disease. And nothing I ate in the hospital could have contributed to it if I had.

Hospital food is not great, but I always devoured it hungrily. Why? Because they give you so little of it. Even after a year of dieting, I was at least accustomed to eating until I was full. In the hospital, I was always hungry because the serving sizes were so puny: for breakfast, a clump of eggs the size of my big toe (and about as tasty); for lunch, soup and a slice of bread; for dinner, some "hot" dish that I generally would have found gross, but which I devoured happily because I was starving! On my birthday, the best present my wife brought me was a foot-long Subway sandwich. I savored it...and wanted more. Every morning I was in the hospital, I was weighed. The day I arrived, I tipped the scales at 241 pounds; they day I left the hospital, I weighed 227 pounds. Some of the weight loss was due to losing muscle mass because I was not exercising as I had been, but most of it was due to lack of food! But, I had finally reached my original weight loss goal.

While I was in the hospital, my wife had a t-shirt made that said "Kardiac Kid" on the front. Kardiac is a purposeful misspelling of the word cardiac, which means relating to the heart; Kid is there because I had a heart attack at such a young age...and maybe because I am frequently pretty childish. The shirt perfectly reflects my sometimes morbid sense of humor, and I knew even then that if I couldn't laugh in the face of fear, I probably wouldn't live much longer.

I left the hospital with many bottles of medications. Strangely enough, it was the medicine that put me back in the hospital seven days later. One of the drugs they had given me was to keep my blood pressure very low. It worked too well. I woke up in the middle of the night to use the bathroom, and the next thing I knew I was in the back of an ambulance again! It seems that I passed out in the bathroom and crashed through the shower door. My wife found me twitching in the tub and, thinking it was another heart attack, called 911. Doctors, however, quickly established that it wasn't my heart that caused me to pass out, but all the medication that was floating around in my system. Just to be sure, they kept me overnight and sent me home again the next day, with orders to stop taking many of the medications I was given the week before.

I spent the rest of the summer feeling sorry for myself, wondering Why me?, and being angry at the unfairness of it. I had worked so hard to be healthy, and I ended up having a heart attack anyway. And, I was scared a lot. Each little twinge of pain anywhere on my upper body always caused panic. I always thought it would be another attack. It never was, but I was terrified most of the time. I had been clearly reminded of how quickly life can change...or end. I didn't exercise anymore because my last workout had almost killed me, so I was scared of that too. It sucked!

By the time school started up again in the fall, I was sick of being scared, and I slowly began to get back into an exercise routine. I vowed to quit feeling sorry for myself, and I committed to myself that I had a future; I'd better quit living like I was dying. Had it not been for the help of Eileen, my wife, I probably would have just faded into miserable oblivion. I scared her terribly (twice), but she helped me get back on my feet. Although it's my story, she's the hero.

Twelve years have passed since that day in 1993. So far, I haven't had any more heart trouble, and I still try to exercise every day; although my diet isn't nearly as radical as it used to be. Every year since then, I have worn my Kardiac Kid shirt on May 29th and told this story to my classes. (Updated info: The shirt has become so ratty that I don't actually wear it anymore, but you can see it by clicking here.) The reason I do this is so that maybe some of you can learn something that will be more meaningful to you in life than commas and pronouns. Yes, commas and pronouns are important, but not as important as LIVING -- making the most of "your one wild and precious life." So here's what I want you to get from this:

1. Start Now: Live Healthily! If you never get overweight to begin with, you'll never have to lose weight later. If you don't start smoking young, you won't have to quit smoking later. If you get in the habit of exercising regularly now, it will never be something you dread. If you train yourself to like healthful food (i.e. vegetables and fruits), you won't clog your arteries with junk food. You are still young enough to make choices that will make your later life much more pleasant. If there are health-related things about yourself that you want to change, you can still do it. Don't wait until you've had a heart attack to turn your life around.

2. Appreciate Your Life! I see a lot of junior high students who spend way too much time complaining and being angry about trivial things that won't make any difference later in life. I know you've heard it a million times before, but it is true: Life is precious. Don't waste it being mad about things that don't matter or doing things to yourself that will impair you later. Take care of yourself and take care of those around you. Enjoy it...because you never know when it'll be over.

Thanks for a fun year! Have a great summer!

(And in case you missed it up above, read the disclaimer now.)

*<%^) Mr. T

P.S. Try the Kardiac Quiz!

P.P.S. Special thanks to my medical editor, Dr. Allen Francis, for telling me the names of all the drugs, machines, and procedures.

© 2018 -- Updated Again May

23, 2018

© 2017 -- Updated Again May

22, 2017

© 2007 -- Updated May 21, 2007

Original version written circa 1999.